Looks like everyone is working for Sequoia the VC

Seems like a little ruckass happening on the West Coast as many angel investors have been acting as scouts for Sequoia, so founders maybe don’t really know where there Angel money was really coming from…….Walter White maybe?????

http://www.wsj.com/…/secretive-sprawling-network-of-scouts-spreads-money-through-silicon-valley

Here is a copy of the article

Startup investor Jason Calacanis took a $25,000 gamble five years ago on a company almost no one had heard of called UberCab. That investment in what is now Uber Technologies Inc. has ballooned to roughly $110 million.

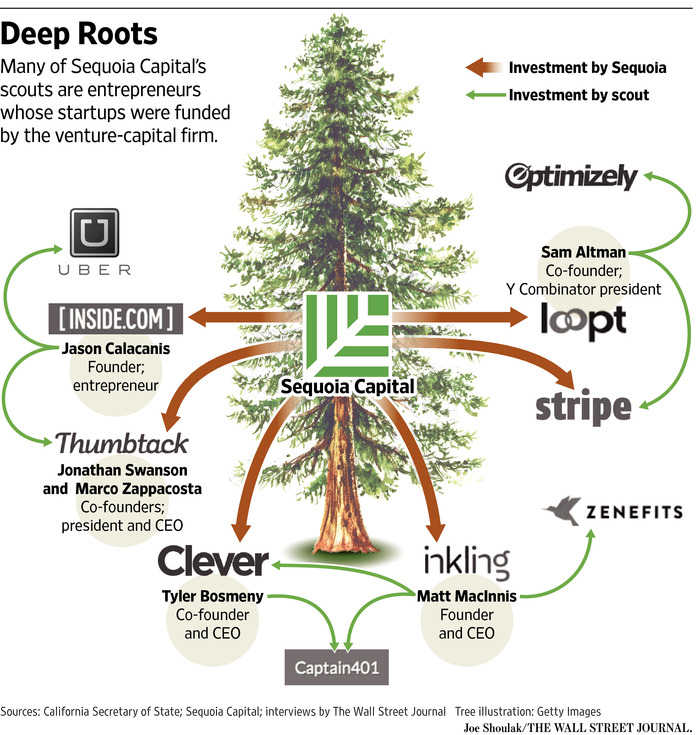

Mr. Calacanis has never said publicly where the money came from: Sequoia Capital, one of Silicon Valley’s biggest venture-capital firms. Since 2009, Sequoia has funneled millions of dollars to scores of well-connected entrepreneurs, academics and other people known as scouts.

Scouts invest the money in startups and keep their eyes and ears open for ideas that Sequoia might like. Mr. Calacanis introduced Thumbtack Inc.’s founder to a partner at Sequoia, which bought a stake in the local-services website that has since surged 50-fold, research firm VCExperts estimates.

Thumbtack’s founders now steer tips to Sequoia, too. “Sequoia had been great to us, so we were happy to send other high-quality entrepreneurs their way,” says Marco Zappacosta, chief executive of Thumbtack. He has made a few startup investments of his own using Sequoia’s money.

The secretive ecosystem of cash and connections is an unusually powerful example of how venture-capital firms try to gain an edge in the never-ending hunt for the next blockbuster. That search has gotten trickier now that some startups with sky-high valuations are hitting turbulence.

Advertisement

Most of Sequoia’s scouts are entrepreneurs whose startups were funded by the firm. That means they know a lot about what Sequoia is looking for and will recommend the firm to other entrepreneurs.

Forging tight relationships that generate new deals for venture-capital firms is more important than ever as the cost of creating startups falls. The resulting acceleration in company launches has made it harder for venture-capital firms to identify the best opportunities as startups emerge. And competition is growing as new investors who are flush with capital invade the technology world.

Sequoia has been a mainstay of the venture-capital establishment for decades. Based in Menlo Park, Calif., on Sand Hill Road, the Main Street of Silicon Valley’s venture-capital industry, Sequoia made early bets on many of today’s tech titans, including Apple Inc., Google Inc. and Cisco Systems Inc.

It was the only venture firm that backed messaging company WhatsApp, sold to Facebook Inc. last year for $22 billion. Sequoia invested about $60 million for a stake valued at $3.5 billion in the deal. Sequoia now owns stakes in 33 private, venture-capital-backed companies valued at more than $1 billion apiece, more than any other venture-capital firm.

Opening doors

Sequoia’s track record opens lots of doors, and the firm opens even more with its careful cultivation of scouts.

The network includes Dropbox Inc. Chief Executive Drew Houston, the three co-founders of Airbnb Inc., Facebook executive Mike Vernal, professors at Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley, and a daughter of Sequoia’s managing partner, Douglas Leone, according to documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

Sequoia also invited John and Patrick Collison, the Irish brothers who co-founded Stripe Inc., to become scouts, but they declined. The five-year-old online-payments company got an early investment from another scout, Sam Altman, the president of tech-startup incubator Y Combinator. Sequoia was an investor in his previous company, Loopt.

Mr. Altman later helped Sequoia seal its own investment in Stripe, according to the venture-capital firm. In July, Stripe said it had raised new funding that values the company at $5 billion.

In all, Sequoia’s scouts have put money into dozens of startups, according to documents reviewed by the Journal and interviews with scouts. The Journal couldn’t make an exact tally because the investments are scattered and Sequoia officials declined to discuss the program’s full scope.

“Everybody in the business tries to generate proprietary deal flow,” says Roelof Botha, the Sequoia partner who heads the scouts program. “That’s part of the challenge in our business: How do you become distinctive in the mind of an entrepreneur?”

Mr. Botha adds: “Hopefully, [a scout investment] means that we have a better-than-otherwise opportunity to meet that company at some point and evaluate whether it might be a good fit for us.”

If a scout’s investment is successful, the vast majority of gains are shared by the scout and Sequoia’s limited partners, Mr. Botha says. Other scouts and Sequoia partners themselves get a small piece of the gains.

Most of the gains since the scout program was created in 2009 are paper gains, not actual profits, Mr. Botha adds.

Sequoia says it instructs scouts to tell startups in which they invest where the money is coming from. But the firm tries to hide the investments from rivals by making them through limited liability companies with odd names. The names include Dragonsteed LLC, Vermillistock LLC and Rocketbooster LLC.

Keeping a low profile is important because Sequoia doesn’t want to jeopardize the future fundraising prospects of startups that previously got money from a scout. It would look bad if everyone knew that Sequoia decided not to invest an even larger amount in a later funding round.

“I don’t like the word ‘secret,’” Mr. Botha says. “I think we have just been discreet about the program all along.”

The existence of Sequoia’s program was described in 2012 by tech blog PandoDaily. Few scout names or other details have been disclosed.

The Journal identified a total of 78 scouts—or 73 men and five women—from incorporation records filed in California, other documents and interviews. In addition, scout names are listed on documents for 44 different limited liability companies. All but two are registered to Sequoia’s headquarters address.

Sequoia confirmed the names of a handful of scouts. When contacted by the Journal, many scouts confirmed their participation or declined to comment.

Some people in the documents say they are no longer active scouts or haven’t made investments. Mr. Botha says Sequoia is looking for new recruits.

Like other venture-capital firms, Sequoia also works college campuses. In addition to a small number of professors who are scouts, a separate team of unpaid students at Stanford, Harvard University, Columbia University and other elite colleges is on the lookout for promising ideas and entrepreneurs.

The next Zuckerberg

“VCs want their brand names on campuses,” says Daniel Liem, who says he was a Sequoia scout while studying computer science at Stanford. “They want to find the next Zuckerberg or Spiegel,” Mr. Liem adds, referring to the founders of Facebook and Snapchat Inc.

Mr. Liem now works at FiscalNote Inc., a startup that uses data-crunching and artificial intelligence to forecast legislation.

Sequoia’s scouts usually invest about $30,000 at a time and are given initial access to about $100,000 a year. Mr. Botha says the amount can grow if scouts identify even more hot ideas.

To fill its pool of scouts, Sequoia turns mostly to the founders of companies already backed by the venture-capital firm or a select group of computer-science professors. Entrepreneurs often reach out to those people for advice long before approaching any venture-capital firms.

For scouts, the appeal is membership in an elite club and free money to make seed investments, which they might not be able to afford.

Sequoia’s program is “a great way to be involved in the startup [and] angel community before I have the means to do so myself,” says Steve Garrity, co-founder and chief technology officer at Hearsay Social Inc. Sequoia owns a stake in the media technology firm.

Mr. Botha says Sequoia’s name is included in wire transfers to recipients. Two recipients say they knew the money came from Sequoia, but two others say they had no idea about the source until a Journal reporter told them.

“Now I think of my company as having a Sequoia radio collar on it,” says an angel investor who was disappointed to learn that Sequoia got a stake through a scout in one of the companies where he is an investor.

For most entrepreneurs and startups, though, cash is a tie that binds. Matt MacInnis left Apple in 2009 after seven years to start digital-publishing company Inkling Inc.

Sequoia invested in Inkling about a year later. After that, Mr. MacInnis says, he was recruited to the scout program by Bryan Schreier, a Sequoia partner.

Mr. MacInnis decided to invest in Clever Inc. with money from Sequoia and out of his own pocket. The educational software firm was launched by friends who worked with him on the Harvard Crimson newspaper, including Tyler Bosmeny, Clever’s co-founder and CEO.

When Mr. Bosmeny was ready to seek a new round of funding, Mr. MacInnis connected him with Mr. Schreier at Sequoia. The venture-capital firm led a $10.3 million investment round in Clever in 2013 and was part of a $30 million fundraising later.

Mr. MacInnis says he was a “good skid greaser.” Now Mr. Bosmeny is a Sequoia scout, too, recently investing with Mr. MacInnis in Captain401, a startup that helps businesses set up 401(k) plans, according to Mr. MacInnis.

Other scout investments by Mr. MacInnis include Zenefits Inc., a human-resources software provider valued in its <a ” href=”http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2015/05/06/zenefits-tagged-with-4-5-billion-valuation-after-just-two-years/” target=”_self”>last funding round at $4.5 billion. Sequoia hasn’t made an additional investment in Zenefits.

Scouts are a “very early warning system, like having a bunch of little satellites installed across the Valley, picking up blips on the radar,” he says.

Omar Hamoui became a scout in 2009 while he was CEO of AdMob Inc., a mobile advertising startup backed by Sequoia. Google bought AdMob for $750 million, a big windfall for the venture-capital firm. Mr. Hamoui became a partner at Sequoia in 2013.

When Sequoia turned 40 years old in 2012, Mr. Calacanis thanked the firm on his Google+ page for helping him get started as an angel investor. Those investors generally are affluent individuals who back fledgling companies with their personal funds.

Mr. Calacanis was one of the earliest scouts and ran an online news startup called Inside.com, in which Sequoia had invested.

The $25,000 from Sequoia that Mr. Calacanis sank into Uber was part of the company’s first fundraising round, which raised less than $2 million.

Since then, Uber’s total funding has swelled to more than $8 billion. Uber was last valued at $51 billion, making it the world’s most highly valued private tech company. Sequoia’s piece of the original $25,000 stake now is likely worth more than $40 million.

Mr. Calacanis says he hasn’t sold any Uber shares. Sequoia hasn’t invested in Uber since then.

Mr. Calacanis also plowed scout money into Thumbtack, the local-services website.

The investment was made a few months after Mr. Zappacosta pitched the startup during a steakhouse dinner in San Francisco organized by Mr. Calacanis, according to the Thumbtack co-founder.

Mr. Calacanis later introduced Mr. Zappacosta to Mr. Botha, the Sequoia partner in charge of the scouts program. Mr. Botha also was a director of Inside.com.

Mr. Zappacosta says Mr. Calacanis urged him later to take a direct investment from Sequoia. “There are times they are going to be hard on you, but that’s what you want,” Mr. Zappacosta recalls being told. “They’re going to push you to be better.”

In September, Thumbtack’s valuation rose to $1.3 billion.

Mr. Zappacosta says he didn’t know for three years that the initial investment from Mr. Calacanis was made with Sequoia’s money. He says the secrecy doesn’t bother him.

“At the time, [Sequoia] had rules about not wanting to divulge that it was the source [of scout] funds,” he says. “Now they want you to tell the founder.”

Scouts propose new investments by submitting a short questionnaire about the startup to Sequoia, which rarely says no. It makes sure the company is based in the U.S. and not in a controversial business like guns or alcohol.

Other scouts sometimes get emails offering them a chance to “follow on” with an investment, says someone who got one of the emails.

Scouts also have chances to hobnob with one another at annual meetings. Mr. Botha says the events build a “sense of community.”

Last year, a few dozen scouts ate dinner at tables in Mr. Botha’s backyard in Los Altos Hills, Calif., chatting and presenting data about some of their investments, say people who were there.

Mr. Botha later sent an email with a link to photos from the evening, according to a copy reviewed the Journal. He asked the scouts to keep Sequoia in mind and thanked them for being part of the firm’s “family.”

http://www.wsj.com/…secretive-sprawling-network-of-scouts-spreads-money-through-silicon-valley

Doug